Background

• Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based therapy intended to treat a range of symptoms related to chronic emotional and behavioral dysregulation across different domains of functioning (Bedics et al., 2015; Brodsky et al., 2017).

• In DBT, the pretreatment phase focuses on setting goals that align with building a life worth living (Coyle, et al. 2019), which lays the foundation for each patient’s commitment to treatment (Bolton & Scherer, 2003).

• This pretreatment commitment is especially important for adolescents, who may have additional difficulties with executive function and future-oriented thinking.

Current Study & Methods

• The current study focuses on DBT for adolescents (DBT-A) and specifically examines how adolescent and parental commitment to treatment relate to outcomes.

• Hypotheses: Greater commitment to treatment, reported by the adolescent, as well as their perceived commitment from their caregivers, would be related with improved treatment outcomes.

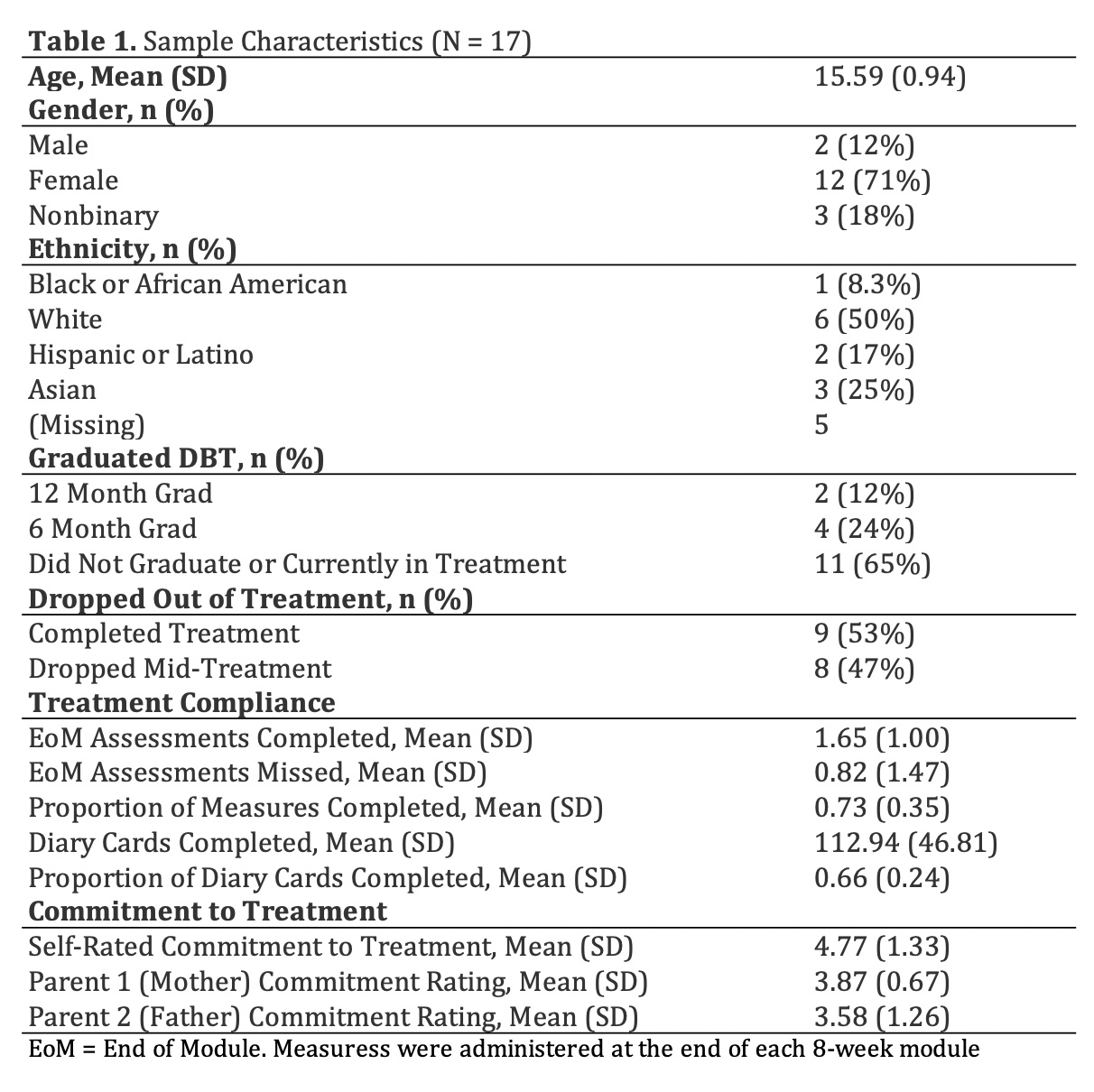

Participants

• N = 17 adolescent DBT patients at an outpatient private practice and training institute in Southern California during the COVID-19 pandemic.

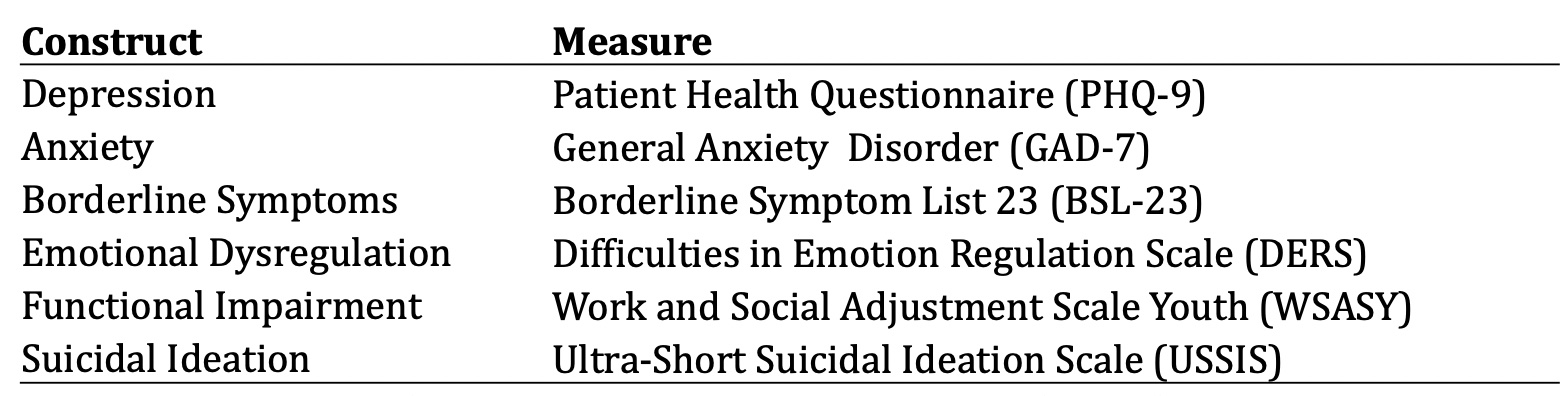

Measures

• Participants completed measures at intake and every two months throughout treatment. *Not all participants completed treatment*

Adolescent ratings of skills group acceptability (proxy for self-rated commitment)*

1. This skills group is helpful.

2. This skills group is acceptable.

3. This skills group meets my needs.

4. In this module, I’ve seen improvement.

Adolescent ratings of caregivers’ commitment to treatment**

1. This grown-up understands that they play a role in the problems I’m working on in therapy.

2. This grown-up is practicing using skills.

3. This grown-up is working to change their part of the problems I’m working on in therapy

4. This grown-up knows how to validate me when I’m struggling.

* Item responses Likert style from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree)

** Item responses Likert style from 1( Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree)

Analysis

• Multi-level models were fit to examine the within- and between-person associations of treatment outcomes with adolescents’ ratings of their own and their caregivers’ commitment to treatment.

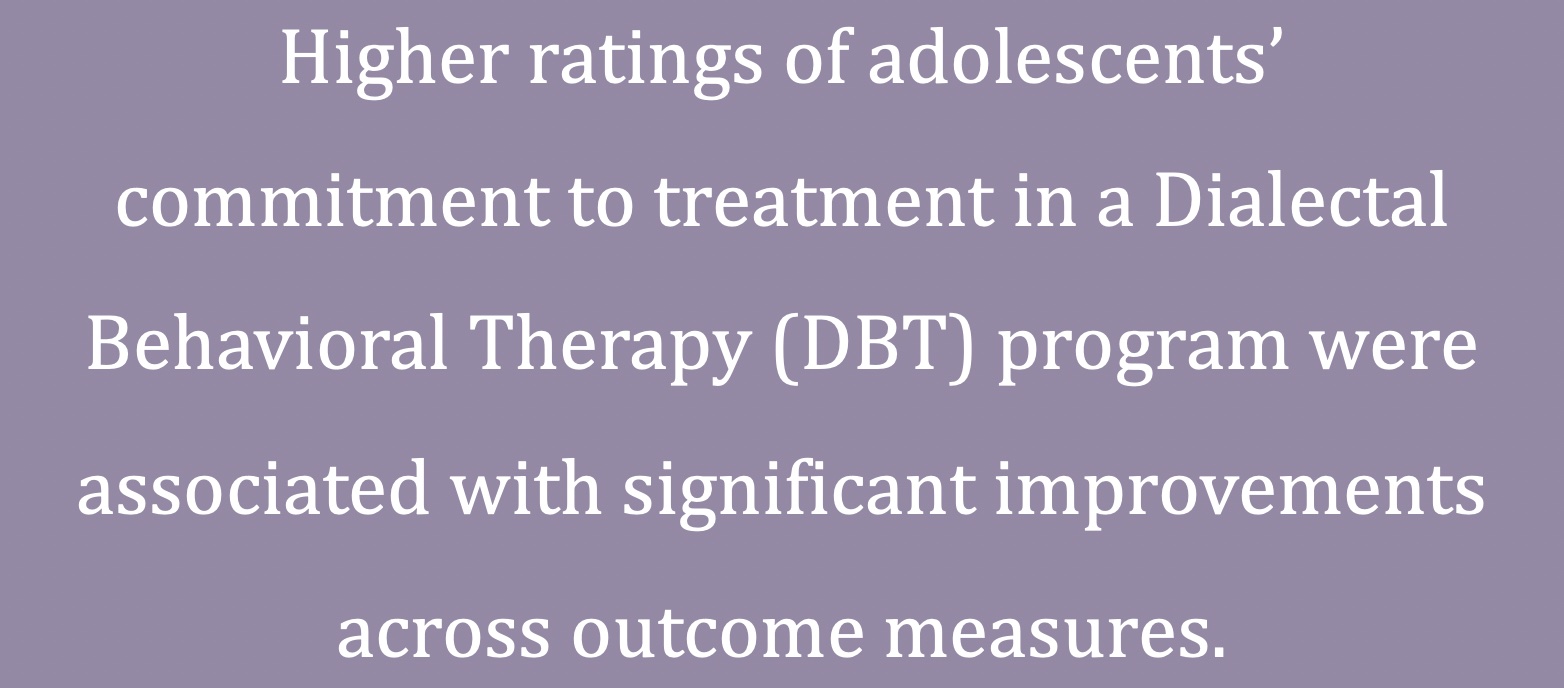

Results

• Results of the multi-level models showed that higher adolescent ratings of self-commitment to treatment were associated with significant improvements for all outcomes measured (all ps < .05). Adolescent ratings of their caregivers’ commitment were not associated with treatment outcomes.

• For all outcomes: overall treatment outcomes improved for every unit increase in self-commitment (main effect)

• For the USSIS, in addition to the main effect of self- commitment on improved outcomes, the longer participants were in treatment, the greater their improvement (time by self-commitment interaction)

Discussion

• As hypothesized, more ‘buy-in’ or commitment from adolescents was associated with improvements across many treatment outcomes, including depression, anxiety, borderline symptoms, emotional dysregulation, and suicidality.

• However, contrary to our hypothesis, adolescents’ perception of their caregivers’ willingness to commit to treatment was not significantly related to treatment outcomes.

• It’s quite likely that the effects of parental commitment are actually “priced in” to adolescents’ self-ratings of commitment

• While the small sample and uncontrolled study does not have enough power to detect meaningful differences, the results suggest that adolescents’ own commitment, but perhaps not necessarily their caregivers’, is a critical contributor to treatment success.

• Future research might examine other factors that contribute to adolescent commitment to DBT.

Research conducted by: Ariela H. Rabizadeh, Psy.D., Rachael Robinson, B.A., Saad Iqbal, B.A., Liora Rabizadeh, B.A., Tonia De Barros Barreto Morton, B.A., Robert Montgomery, M.A., and Lynn McFarr, Ph.D.

References

- Bedics, J. D., Atkins, D. C., Harned, M. S., & Linehan, M. M. (2015). The therapeutic alliance as a predictor of outcome in dialectical behavior therapy versus nonbehavioral psychotherapy by experts for borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy, 52(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038457

- Bolton Oetzel, K., & Scherer, D. G. (2003). Therapeutic Engagement With Adolescents in Psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 40(3), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.40.3.215

- Brodsky, B.S., Cabaniss, D.L., Arbuckle, M. et al. Teaching Dialectical Behavior Therapy to Psychiatry Residents: The Columbia Psychiatry Residency DBT Curriculum. Acad Psychiatry 41, 10–15 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596- 016-0593-0

- Coyle, T. N., Brill, C. D., Aunon, F. M., Peterson, A. P., Gasser, M. L., Kuehn, K. S., & Harned, M. S. (2019). Beginning to envision a life worth living: An introduction to pretreatment sessions in dialectical behavior therapy. Psychotherapy, 56(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000205

- Perepletchikova, F., Axelrod, S.R., Kaufman, J., Rounsaville, B.J., Douglas-Palumberi, H. and Miller, A.L. (2011), Adapting Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for Children: Towards a New Research Agenda for Paediatric Suicidal and Non-Suicidal Self-Injurious Behaviours. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 16: 116-121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475- 3588.2010.00583.x